Generating Bitcoin Keys From Scratch With Ruby

15 Mar 2015I’ve recently been looking into some newer features in the bitcoin protocol and feeling a little overwhelmed. I’ve only ever worked with higher level abstractions of the protocol via libraries. In order to get a better understanding of the fundamentals I started reading as much as I could. I found a lot of articles but I felt like each one was missing pieces that helped me understand what was going on. I decided I would try to write a bitcoin transaction from scratch (no bitcoin related libraries) and document the process. I used ruby. I like ruby and I knew I wouldnt get much help from Google with it (which is good). My goal was create a bitcoin address, send some BTC to it, then spend that BTC by creating a new transaction and publishing to the network. So far I have only successfully generated keys so consider this part I.

Bitcoin primitives

We aren’t going to talk about mining and the bitcoin network. It’s not really important to understanding how to make a transaction. I expect you to understand bitcoin on a high level. These are the core primitives we are going to explore.

- Private Key

- Public Key

- Address

- Transaction (eventually)

Private Keys

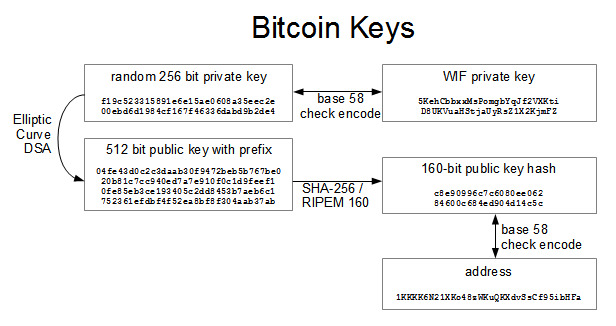

The most important primitive is the private key. All other keys are derived from the private key. Here is a diagram explaining the process for creating keys:

The private key is, in essence, just a really big random number (256-bits) which can easily be generated offline with a sufficient source of randomness. Because of that, the public key and the address can also be generated offline. Of course, due to the laws of public key cryptography, it is impossible* to derive the private key from the public key or the address. Bitcoins are tied directly to the private key. The owner of the private key cotrols the bitcoins. Because of this, secrecy and security of the private key is of utmost importance. In general, the only thing that you should ever willingly expose is the Address. You don’t even want to reveal your public key until you have to.

Generating Private Keys

Like I said before, the private key is just a 256-bit (32 byte) random number. You can create a private key pretty much any way you can generate random numbers. If you have openssl installed on your machine, try running this command a few times:

$ openssl rand 32 -hex

f9a9c3825fe4f90385763d3a95b85a3c081410367bcb6c15bb550214bf1faf1a

These are valid private keys. You could even flip a coin 256 times, record each result as 0 or 1, then turn that bit array into a hex string that would look just like one from openssl. You can do pretty much anything you can think of as long as your source of randomness is cryptographically secure.

You may be wondering how you can do this offline since if someone were to somehow accidentally generate a private key that you have also generated, they could control the funds on that address. Believe it or not, every time you generate one of these numbers you can very safely bet your life this is the first time the world has seen that number because the keyspace is so massive even when considering the birthday paradox. For this reason, you can safely generate a key offline and be sure that it does not collide with someone else’s key.

Let’s generate a private key in ruby using securerandom. We are going to use another method later but I’ll explain when we get there. This will spit out 256-bit (32 byte) hex strings much like the openssl command above did.

require 'securerandom'

# Generate a 256-bit (32 bytes) secure random number

def generate_key

SecureRandom.hex(32)

endPrivate Key WIF

WIF, the wallet import format is a format for encoding a private key into ASCII space. It uses Satoshi’s own base58check encoding. You may wonder why Satoshi wouldn’t just use base64. Here is the explanation:

// Why base-58 instead of standard base-64 encoding?

// - Don't want 0OIl characters that look the same in some fonts and

// could be used to create visually identical looking account numbers.

// - A string with non-alphanumeric characters is not as easily

// accepted as an account number.

// - E-mail usually won't line-break if there's no punctuation to break at.

// - Doubleclicking selects the whole number as one word if it's all alphanumeric.This encoding also includes a checksum using SHA-256 which can very quickly verify the integrity of an Address and potentially even allow you to correct it. This is a pretty responsible implementation considering one misplaced character could cost you all your bitcoins.

Let’s look at some ruby code to do base58. I took this from the utils in the bitcoin-ruby project:

def int_to_base58(int_val, leading_zero_bytes=0)

alpha = "123456789ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijkmnopqrstuvwxyz"

base58_val, base = '', alpha.size

while int_val > 0

int_val, remainder = int_val.divmod(base)

base58_val = alpha[remainder] + base58_val

end

base58_val

end

def encode_base58(hex)

leading_zero_bytes = (hex.match(/^([0]+)/) ? $1 : '').size / 2

("1"*leading_zero_bytes) + int_to_base58( hex.to_i(16) )

endIn order to do the checksum we will need a function capable of creating a SHA-256 hash from a hex string. Ruby’s digest module comes with this capability:

require 'digest'

# SHA-256 hash

def sha256(hex)

Digest::SHA256.hexdigest([hex].pack("H*"))

endNow the checksum is simply the first 4 bytes of the twice SHA’d hex string (The WIF format requires doing the double SHA).

# checksum is first 4 bytes of sha256-sha256 hexdigest.

def checksum(hex)

sha256(sha256(hex))[0...8]

end

PRIV_KEY_VERSION = '80'

def wif(hex)

data = PRIV_KEY_VERSION + hex

encode_base58(data + checksum(data))

endThe WIF format also requires that the first byte be the WIF version. Here we have set it to 0x80. It would be 0xef if we were using testnet.

Now let’s make some WIFs!

# Remember #generate_key returns a new 256 bit

# private key as a hex string

puts wif(generate_key)

# => "5JNHWufka5pPaZ2SViwXEUARU67aqZrqJvB6bmj9Xd1rC91vo31"

puts wif(generate_key)

# => "5K5KeFgcbNzppWmz6zqVDe1NmWX4hLMdcDz6LtaoFCfLmB4dZwu"

puts wif(generate_key)

# => "5K14yHUGCQkTm9qRgVVgEpBXHdF1kcZefksprfTRJSd85NwdWiY"According to the spec, a base58 encoded private key must start with either '5H', '5J', or '5K' and these all do. These are valid WIFs you could import into your wallet software now if you wanted! Please don’t do that though :)

Deriving Public Keys

The next step is deriving the public key. Bitcoin uses ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) for it’s cryptographic signatures. I suggest you either know a little about or research the following topics before continuing:

- Public Key Cryptography

- Digital Signatures

- Eliptic Curve Cryptography

Ruby doesn’t really make doing this part easy for us. But, I knew this would be the case coming in and decided that might make using it a good learning experience. There is a great, simple ecdsa library for python but not really one for ruby. I did find this library but the idea of someone implementing their own crypto, and in ruby of all languages, kind of freaked me out. To be fair, he does state in his readme that his library is for learning purposes. My code is also only for learning purposes so I am less concerned about security but I am instead concerned about an experimental library generating something in a weird way. The reason is that, since bitcoin is a cryptographic protocol, it’s very opaque and if even one bit is off it could result in errors with no explanation of what the problem is.

Because of these reasons, I chose to stick with openssl. It has a bad reputation right now (and an even worse API) but it at least has a lot of eyes on it and I can trust that it isn’t going to do anything too weird. It’s also default with ruby so there is no need to install any third party libraries.

We’re going to be using the EC class in the OpenSSL::PKey module. Because it generates it’s own private key we will no longer be using our generate_key method.

require 'openssl'

# Bitcoin uses the secp256k1 curve

curve = OpenSSL::PKey::EC.new('secp256k1')

# Now we generate the public and private key together

curve.generate_key

puts curve.private_key

# => #<OpenSSL::BN:0x007f3e2e63e520>

puts curve.public_key

# => #<OpenSSL::PKey::EC::Point:0x007f3e2e55fdc0We now have our public and private key but they aren’t really in a good format for us to work with. We’d prefer hex strings.

The private_key is of the type OpenSSL::BN or (Big Number). It is what it sounds like, a big integer. Here is an example:

curve.private_key.to_s

=> "59349466814215569740836827258207701086591329864926689993285822531257454935241"Ruby’s to_s takes a base. So to get the hex string we just have to ask for base 16 and we get back our 32 byte key in hex format:

curve.private_key.to_s(16)

=> "83369B99791B5F3E7008C897CFA3AE4899BD2E256E4EE0D3020501977F35BCC9"The public_key is of the type OpenSSL::PKey::EC::Point because in elliptic curve crypto, the public key represents a point on the curve. The Point class has a method to_bn we can use to convert it to a Big Number. This will be a 65 byte number. The first byte will be 0x04. The next 32 will represent x, the next 32 will represent y. Fortunately this is the format Bitcoin wants it in so we just need to turn it into a hex string:

curve.public_key.to_bn.to_s(16)

# => "04FDA9AD13F927257D26365DF9ED5B8734B2468EFBB0DD29037AE18F08CF7442FD0139355A1EAD51932E0CBBC43F2D1DDDE2F287FD4A0E06F054E3360243320CA1"Signing and verifying messages

Before we move on to generating the address let’s explore the properties of this curve object. As you should know, a digital signature allows us to sign and verify data. Let’s say we have some data in string format:

message = 'Hello World!'I want to pass this message on to someone else but I want to provide proof that:

- I am the actual author of the message (someone has not just forged my signature and pretended to be me)

- The message has not been altered in transit

This is generally what would be called authentication in crypto and using a signature algorithm can help provide this proof. “Signing” our data is a function of our private key and the data. In this case the curve object has abstracted that away. Just know that it uses the private key under the hood:

signature = curve.dsa_sign_asn1(message)

# => "0F\x02!\x00\x8C\x18b\xF1\x96\xC7V\bARH\xA3\x05ES\v\xFF\x8F_D7\xE10\x16\xD0>UI5\f\xAA\xEE\x02!\x00\xB2h\xC2\b\xFE\x87uD\x98\xD7Z\x94YL\xF63\xC4\x06\x1C\xE1\x9E\x15\xAE\x05\xAF}5\xC9\x95\xEE\x9C\x97"The result here is a signature in ASN1 format.

Now, given our public key, the message, and the signature, a reciever of the message can verify that the message was in fact signed by our private key and has not been tampered with. We call this “verification” of the message.

First suppose we export the big number of the public key.

pub_key_bn = curve.public_key.to_bnAlso suppose the receiver of the message already has this on his computer and we have verified it is my public key.

# Now let's pretend we just sent [message, signature] to

# the receiver of our message and this is now their computer

# The reciever creates their curve object using the same secp256k1 group

group = OpenSSL::PKey::EC::Group.new('secp256k1')

curve = OpenSSL::PKey::EC.new(group)

# They only have the public key (point) and set it

curve.public_key = OpenSSL::PKey::EC::Point.new(group, pub_key_bn)

# See, no private key

curve.private_key

# => nil

# Now they can use the public key to verify the message

curve.dsa_verify_asn1(message, signature)

# => trueIn order to drive this home, let’s see what happens if we modify the message:

message << '!'

curve.dsa_verify_asn1(message, signature)

# => falseI leave it to the reader as an exercise to see that modifying the public key or the signature also results in a failure to verify the message.

Generating an Address

The public key is the address for all intents and purposes but for convenience and some security reasons we must first compute the Public Key Hash [a 160 bit hash of the public key]. Then we base58check encode that for integrity and readability. This base85 encoded result is the Address.

The Public Key Hash is just a SHA-256 hash of the public key which is then run through RIPEMD-160. We already have a sha256 function, so let’s make one for RIPEMD-160. Ruby provides this hashdigest in the same Digest module we used with SHA-256.

# RIPEMD-160 (160 bit) hash

def rmd160(hex)

Digest::RMD160.hexdigest([hex].pack("H*"))

endNow the public key hash:

# Turns public key into the 160 bit public key hash

def public_key_hash(hex)

rmd160(sha256(hex))

endUsing our public key from earlier, the result should look something like this:

pub_key_hex = curve.public_key.to_bn.to_s(16)

# => "04FDA9AD13F927257D26365DF9ED5B8734B2468EFBB0DD29037AE18F08CF7442FD0139355A1EAD51932E0CBBC43F2D1DDDE2F287FD4A0E06F054E3360243320CA1"

public_key_hash(pub_key_hex)

# => "291b6b709bd2917afd72b490eda1cf3ffd272b53"Now that we base58check encode the public key hash to get the address:

ADDRESS_VERSION = '00'

def generate_address(pub_key_hash)

pk = ADDRESS_VERSION + pub_key_hash

encode_base58(pk + checksum(pk))

end

generate_address(public_key_hash(pub_key_hex))

# => "14kMZ24Zm8ARfotFdyuJvKi1PpZ2bvfdjC"And there is our bitcoin address. Our address version here is 0x00. For testnet it’s 0x6f. The spec says that version zero addresses should start with 1.